This article is intended for anyone suffering from damage to their articular cartilage and their families who would like to find out about autologous chondrocyte implantation, as well as anyone interested in cartilage problems.

If you suffer from joint pain, you’re not alone. Each year, more than 50 million people visit their doctors because of joint pain — half of them with a damage of the articular cartilage.

On this website, you can find useful, updated information on specific cartilage-related conditions and possible treatments options, written by world-renowned experts in this field, helpful patient information to read and download, and other useful resources

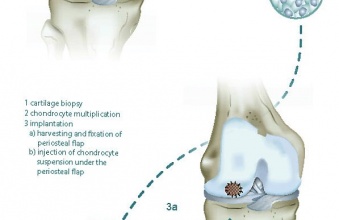

The choice of procedures depends on the size and location of cartilage defect. Larger defects are typically treated with autologous chondrocyte transplantation, osteochondral allograft transplantation, or newer synthetic or natural scaffolds which may require open incisions. Smaller defects in specific locations may be treated with enhanced bone marrow stimulating techniques, autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI), or osteochondral autograft transfer which may be completed through the arthroscope. There is also a chapter for conservative treatments options and rehabilitation after cartilage repair.

Intended Audience for this Website

People of all ages can suffer from cartilage complications, whether due to ‘wear and tear’ or injury. While the former is much more common in middle-aged patients, and even more so in women, injuries to the joints, such as trauma or accidents during active sports, can affect any age group or gender. Careers requiring repetitive or intense motion can increase the risk of developing cartilage problems, but there are several other risk factors, including age, weight and genetic predisposition.

What is Cartilage Repair?

On this website, we focus only on articular cartilage repair treatments, which means the restoration of damaged hyaline cartilage in the joints. Cartilage repair and regeneration is a treatment for joints that have damaged cartilage but are otherwise healthy. Typically, these procedures are recommended for cartilage damage or deterioration caused by:

Injury or trauma, including sports injuries or repetitive use of the joint Congenital abnormalities – abnormalities a person is born with (for instance misalignment) – that affect normal joint structure Hormonal or idiopathic disorders that affect bone and joint development, such as osteochondritis dissecans (OCD). There are several types of new and modern procedures for cartilage repair and regeneration techniques that are designed to heal the cartilage by filling the cartilage defect (pothole) with repair tissue.

What is not covered in this Website?

There are several types of bone and joint pain, each with many potential sources or etiologies. This site is not intended for people who suffers from rheumatoid arthritis (RA), gout, avascular necrosis (AVN), and cancer within bones, osteoporosis and other inflammatory or autoimmune diseases.

Acknowledgements

To the Mäxi Foundation:

This website project would not have been possible without the substantial support of the Swiss “Mäxi Foundation”. The ICRS would like to express a deep gratitude for this very generous contribution to the International Cartilage Repair Society and the respective patient community, making it possible to provide updated information about cartilage damage and cartilage repair technologies free of charge to all interested persons.

To the Authors & Contributors:

The following world-renowned experts in cartilage repair & cartilage research have contributed to the extensive content of this website: Stephen Abelow (USA), William Bugbee (USA), Susan Chubinskaya (USA), Brian Cole (USA), Stefano Della Villa (IT), Chris Erggelet (CH), Jack Farr (USA), Ralph Gambardella (USA), Michael Gerhardt (USA), Wayne Gersoff (USA), Alan Getgood (CA), Alberto Gobbi (IT), Laszlo Hangody (HU), Oliver Kessler (CH), Elizaveta Kon (IT), Jos Malda (NL), Bert Mandelbaum (USA), Tom Minas (USA), Kai Mithoefer (USA), Stefan Nehrer (AT), Lars Peterson (SE), Scott Gillogly (USA), Holly Silvers (USA), Jason Theodosakis (USA) and Kenneth Zaslav (USA)

To anyone else who contributed to this important project

ICRS Office Staff, Medical Writers, Committees, Illustrators and Web Developers, etc.

Terms of Use

These terms of use, together with our Privacy Policy collectively, these “Terms of Use”, governs access to and any use of the website cartilage.org and any sub-sites (the “Website“), including any content, functionality and services offered on or through the Website. By using the Website or by clicking to accept or agree to the Terms of Use when that option is made available, visitors of the Website accept and agree to bound and abide by the Terms of Use on behalf of all users of the respective computer. Visitors who do not agree with these Terms of Use must not access or use the Website.

International Cartilage Repair Society (“ICRS”) (“we” or “us”) may revise and update these Terms of Use from time to time in our sole discretion. All changes are effective immediately when we post them. Your continued use of the Website following the posting of revised Terms of Use means that you accept and agree to the changes. You are expected to check this page from time to time so that you are aware of any changes, as they are binding on you.

The information on the Website is not intended to treat, diagnose, cure or prevent any cartilage related issues. Always seek the advice of a physician or other qualified health care provider with any questions you have regarding your medical condition.

Privacy Policy

This privacy policy (“Privacy Policy”), together with the Terms of Use for the patient website section, applies to any use of the website cartilage.org and any sub-sites (the “Website”), including any content, functionality and services offered on or through the Website. By using the Website or by clicking to accept or agree to the Terms of Use when that option is made available, visitors of the Website accept and agree on behalf of all users of the respective computer to be bound and abide by the Terms of Use and this Privacy Policy. Visitors who do not agree with the Terms of Use and this Privacy Policy must not access or use the Website.

International Cartilage Repair Society (“ICRS”) (“we” or “us”) is committed to protecting your privacy and ensuring that your personal information is protected. This Privacy Policy explains the types of personal information we collect and how we use, disclose and protect that information.